Executive Summary

In 2021, the federal government introduced a Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care (CWELCC) program, to be implemented through federal–provincial/territorial bilateral agreements. The program followed on the federal government’s budget commitment to provide parents with, on average, $10-a-day regulated child care spaces within the next five years.

With the notable exception of Ontario, along with, to a limited degree for some years, Alberta, child care in Canada has not historically been delivered by municipalities. The CWELCC provides an opportunity for a significantly enhanced role for municipalities to increase access to quality child care.

In this series of papers, the authors examine the ability of municipalities to fund, manage, and deliver child care in response to the increased demand. Martha Friendly reviews international precedents for federally funded and municipally managed and/or delivered child care with a view to learning from their experiences and considers the advantages that a heightened municipal role could play in strengthening Canada’s newest social program. Gordon Cleveland and Sue Colley investigate the roles and responsibilities of the different orders of government and how they will change in light of the CWELCC, with a focus on actions that Ontario will need to take over the next 20 years. Rachel Vickerson and Carolyn Ferns discuss how governments can play a role in addressing the dire need for early child care educators, while Carley Holt proposes a roadmap for municipalities that brings stakeholders together to establish distinct approaches for their communities.

Municipal

Friendly explores how municipalities can become more significant players in boosting access to early learning and child care, considering both public management and public provision as opportunities.

Cleveland and Colley look at the history of the delivery of child care in Ontario, the changes that the CWELCC will bring to the municipal role, and the importance of municipal involvement in provincial planning.

Vickerson and Ferns discuss the importance of staffing; they argue that municipally operated child care provides, on average, better working conditions and wages than private or non-profit care.

Holt provides examples of cities across Canada that have defined a role in supporting accessible, equitable, and high-quality early learning and child care initiatives, and presents a list of seven key actions that municipalities can take to achieve these goals.

Provincial

Friendly notes that the implementation of the CWELCC’s goal of reducing parent fees substantially was met, or nearly met, by all provinces and territories by the end of 2022 – but that this success has driven demand for more child care programs, turning a spotlight on the need for equitable expansion in each province.

Cleveland and Colley provide a list of actions Ontario will need to take over the next 20 years to fully develop the early learning and child care system, including more operational funding, better compensation for educators, loan guarantees for capital expansion for both non-profit and public organizations, and increased subsidies for children with special needs.

Vickerson and Ferns recommend that provinces improve their expansion planning, including removing legislative barriers, and develop province-wide workforce strategies and pay scales for early childhood educators.

Federal

Friendly notes that, until 2021, there was no defined federal role in, or funding for, building a Canada-wide child care system. She reviews international precedents from the European Union, where senior governments provide funding and goals, while municipalities largely manage and deliver child care, based on the principle that services should be delivered by the level of government closest to those who are affected (i.e., subsidiarity).

Cleveland and Colley foresee the necessity for further funding from the federal government to meet the expected demand for child care spaces in Ontario over the next 20 years.

Intergovernmental cooperation

Friendly points to examples of new kinds of partnerships between municipalities and provinces, such as a municipal organization in Manitoba that worked with the provincial government, using provincial and federal funds, to create and construct modular child care centres in rural and First Nations communities.

Cleveland and Colley criticize Ontario’s lack of collaboration with local municipalities in child care planning since signing the CWELCC agreement, and call for the formation of a new provincial body to ensure that Ontario’s Child Care Action Plans reflect municipal knowledge and priorities.

Vickerson and Ferns argue that the federal government should include municipalities in child care policy-making. Involving municipalities in the CWELCC agreements’ intergovernmental meetings and its Implementation Committees would enable them to align child care with other priorities and bring local expertise in operation and system management to the table.

Holt notes the importance of creating a board or committee that focuses on early learning and child care and involves key stakeholders and all order of governments in order to form partnerships and create collaborative, sustainable solutions.

Backgrounder: Municipalities and Child Care

By Gabriel Eidelman and Spencer Neufeld

Gabriel Eidelman is Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream, and Director of the Urban Policy Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Spencer Neufeld has a Master of Public Policy degree from the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Child care is a necessity for millions of Canadian families. More than half of children under the age of six attend either licensed or unlicensed child care.[1] Despite recent progress by the federal government toward developing a universal, Canada-wide child care system, child care and early learning services – often referred to as early childhood education (ECE) – remain the primary responsibility of provincial and territorial governments, as the constitutional division of powers grants provinces jurisdiction over education and related social services (child care does not appear in the 1867 Constitution Act). Less obvious is the role Canadian municipalities play in designing and delivering child care and early learning services in their communities.

This backgrounder outlines the role of municipal governments in the funding, regulation, planning, and provision of child care in Canada. First, we review the extent to which municipalities work independently to provide child care and early learning within provincial legislative constraints. Next, we outline where and how municipalities collaborate with provincial and federal governments in child care policy development and service delivery.

Municipal action within legal and fiscal constraints

Overall, municipalities “do not play a large role in child care Canada-wide.”[2] In most parts of the country, local governments have no formal responsibility for child care. Instead, provinces and territories oversee child care policy, with partial funding from the federal government through both conditional and unconditional grants. Very few municipalities have their own child care policies; even fewer operate their own child care centres, accounting for less than 1 percent of all regulated child care spaces (Table 1).

Table 1: Number of Municipal Child Care Centres and Spaces, by Province

| Province | Centres (% of provincial total) | Spaces* (% of provincial total) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prince Edward Island | 2 (1%) | 90 (1%) |

| Nova Scotia | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| New Brunswick | 3 (<1%) | 97 (<1%) |

| Quebec | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ontario | 109 (2%) | 6,173 (1%) |

| Manitoba | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Saskatchewan | 3 (<1%) | 157 (1%) |

| Alberta | 4 (<1%) | 77 (<1%) |

| British Columbia | 63 (2%) | 2,218 (2%) |

Source: Compiled from Jane Beach, Martha Friendly, Ngoc Tho (Tegan) Nguyen, Patrícia Borges-Nogueira, Matthew Taylor, Sophia Mohamed, Laurel Rothman, and Barry Forer, Early Childhood Education and Care in Canada 2021 (Toronto: Childcare Resource and Research Unit, 2023).

Ontario is a notable exception where local governments have operated or overseen child care centres since the 1940s. As set out in the 2014 Child Care and Early Years Act, municipal governments in Ontario are mandated by law to serve as “service system managers” with primary responsibility for child care and ECE services.[3] The province retains authority to prescribe overall standards related to licensing, health and safety inspections, maximum class sizes, staffing levels and qualifications, wages, and training requirements. Within these bounds, municipalities are responsible for drafting service plans and setting local operational policies, as well as, most importantly, administering financial subsidies to service providers on behalf of the province.

The Act also allows municipalities to operate their own child care premises and early years programming. As of 2021, 16 Ontario municipalities operated 109 child care centres, totalling 6,173 spaces (out of a provincial total of 464,538 spaces for children 0–12 years, including before- and after-school programs).[4] These numbers have declined dramatically in recent decades, down from 18,143 spaces in 1998, due to municipal fiscal challenges.[5] The City of Windsor, for instance, closed all its municipally operated centres in 2010.[6]

In large, single-tier municipalities such as the City of Toronto, child care is overseen by dedicated municipal departments that, in addition to operating their own facilities, oversee dozens of private and non-profit local operators. In two-tier municipalities such as Peel, York, Durham, and Halton, child care is administered, but rarely operated, by the upper-tier regional municipality. In small or rural municipalities, responsibilities are often shared across multiple municipalities via district social services administration boards. All told, Ontario’s 444 municipalities are organized into a total of 47 Consolidated Municipal Service Managers (CMSMs) and District Social Services Administration Boards (DSSABs).

In most parts of the country, local governments have no formal responsibility for child care.

Funding for child care in Ontario is shared between the province and municipalities, formally allocated via a complex formula last revised in 2019–20 that considers demographic figures, cost-of-living indicators, existing service levels, and expansion plans.[7] In practice, however, this formula is as much a product of political negotiations between provincial and municipal officials as of technocratic decision making.[8]

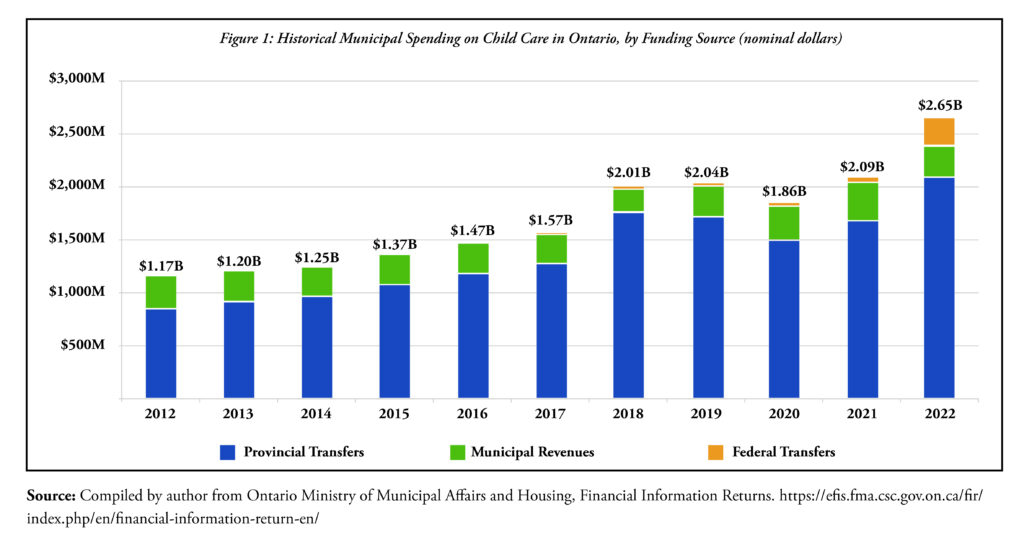

According to Financial Information Return data from the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Ontario municipalities spent $2.7 billion on child care services in 2022 (Figure 1), covering staff salaries and benefits, subsidies for eligible families, and rents and other system management costs. Approximately 78 percent ($2.1 billion) of this total was offset by provincial transfers.[9] Until 2021, the federal government provided less than 2 percent of child care funding. After signing on to the Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care (CWELCC) Agreement in 2022, federal transfers to Ontario rose to 10 percent of overall expenditures (including retroactive payments for the 2021-2022 fiscal year), and are projected to eclipse total provincial funding to the system by the time the agreement expires in 2026.[10] The remainder, in the order of $300 million per year – 11% of expenditures in 2022, is funded via municipal own-source revenues (i.e., property taxes and user fees). Toronto’s net expenditures for child care amount to approximately $90 million per year.[11]

Figure 1: Historical Municipal Spending on Child Care in Ontario, by Funding Source (nominal dollars)

Source: Compiled by author from Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Financial Information Returns. https://efis.fma.csc.gov.on.ca/fir/index.php/en/financial-information-return-en/

Outside Ontario, only a few dozen municipalities operate their own child care centres, mainly in British Columbia. The B.C. Ministry of Education and Child Care is ultimately responsible for child care and early learning across the province, including operational funding and fee subsidies for low-income families. Nevertheless, several municipalities actively engage in child care policy, such as amending zoning bylaws and land use plans to encourage new construction of child care spaces, or placing conditions on the type of child care operators eligible to receive public funding.

The City of Vancouver, for example, has played a “significant voluntary role” in child care planning and funding.[12] In 2022, Vancouver City Council adopted a 10-year child care strategy to expand access to child care across the city – the city’s fourth child care plan since 1990.[13] The strategy defines child care as an essential service, sets out goals to secure more non-profit child care spaces, affirms the rights of Indigenous families to access Indigenous-led care, extends city capital grant programs and nominal lease arrangements for non-profit child care operators, and streamlines planning approvals for non-profit child care centres located within civic facilities (e.g., community and recreation centres), particularly in low-income and under-served communities.

Similarly, the City of Richmond adopted its own 10-year child care strategy, an update to the Child Care Development Policy it first published in 2006. The plan calls for a net increase of 3,741 child care spaces by 2031, to be enabled by a review and update of city bylaws, zoning, and development approval processes.[14] This strategy is in addition to other supportive city policies and programs, such as a child care needs assessment program; a child care development reserve fund, financed through developer contributions, earmarked for creating child care centres in city buildings and on city lands and for covering non-capital expenses such as program development and research; and a child care development advisory committee, which reports to city council.[15]

In Alberta, just four small, rural municipalities currently operate their own child care centres.[16] But this was not always the case. At one time, Alberta’s municipalities both delivered public child care and supported non-profit child care. Edmonton, Calgary, Medicine Hat, Red Deer, and several other municipalities operated as many as 66 child care centres, with thousands of spaces. Many local governments also provided direct subsidies for low-income families. However, in the 1980s, the province took back authority for child care, redirecting operational funding to the for-profit sector. As a result, the municipally operated child care sector in Alberta “has almost entirely disappeared.”[17]

In recent years, Alberta’s largest cities, such as Edmonton and Calgary, have developed some strategies and policies related to child care. For example, the City of Edmonton established the Edmonton Council for Early Learning and Care in 2019, which brings together municipal, provincial, and civil society representatives twice a year to coordinate child care services, with particular emphasis on low-income and vulnerable families.[18] Meanwhile, the City of Calgary recently introduced a new regulation and licensing regime for home-based child care businesses outside the scope of provincial regulations.[19]

Municipal cooperation and coordination with other orders of government

Local governments are rarely included in meaningful consultation or cooperation arrangements between provincial and federal governments. Consider the recent series of CWELCC agreements, negotiated and signed bilaterally between the federal government and all 13 provinces and territories. The agreements, which collectively aim to create 250,000 new child care spaces across the country and reduce parent fees to $10 a day by 2026, mention municipal governments sparingly, and were negotiated without meaningful consultation or input from local governments.[20] Even in Ontario, where municipal “service managers” administer child care services province-wide, and will be expected to develop updated service expansion plans, register licensed operators, and distribute federal funding, municipalities were not invited to the negotiating table.[21]

British Columbia arguably exhibits the most collaborative policy environment. For example, in 2019, the City of Vancouver, the Government of British Columbia, and the Metro Vancouver Aboriginal Executive Council signed a $33 million memorandum of understanding, which sets out joint targets for new child care spaces in the city and includes funds for a dedicated Early Learning and Child Care Planner staff position to support urban Indigenous children and families.[22] This work is supported by the Vancouver Child Care Council, formerly known as the Joint Council on Child Care, which meets twice a year to improve coordination between the City, the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, the Vancouver Board of Education, and Vancouver Coastal Health.[23] British Columbia also recently provided up to $1 million to local governments, through the Union of British Columbia Municipalities, to create new non-profit or public child care spaces in municipal facilities.[24]

Outside British Columbia, however, municipalities seldom collaborate with provincial governments on child care policy beyond routine land use planning and building approvals. For example, in the Quebec system, the provincial government oversees every aspect of child care services, with no role for municipalities. The province distributes all operational funding to non-profit and for-profit providers (known as centres de la petite enfance, garderies, or jardins d’enfants); sets maximum parent fees; approves business licences; conducts health, safety, and quality inspections; and establishes training and certification standards. No municipalities in Quebec operate their own child care centres (nor do any other public authorities), though provincial legislation does allow municipalities to sell, donate, or rent municipal buildings to child care centres free of charge.[25]

Conclusion

All in all, the municipal role in child care is limited, in both scale and scope. Only a small number of municipalities have voluntarily adopted dedicated child care strategies, action plans, or policy frameworks. Those that do choose to engage tend to offer capital grant programs for operators, provide fee subsidies for low-income families, convene child care planning tables or advisory committees, or conduct child care needs assessments.[26]

Ontario is the major exception. There, municipalities are mandated by law to serve as child care system service managers, with primary responsibility for service planning, implementation, and financial administration – as well as involvement to a lesser extent with funding and direct provision, given the majority of services are delivered by not-for-profit and private entities. In no cases, however, are municipal governments treated as equal partners in intergovernmental policy discussions or funding negotiations.

The Role of Municipalities in Canadian Child Care: What Do They Do? What Could They Do? How Could They Make a Difference?

By Martha Friendly

Martha Friendly is the Founder and Executive Director of the Childcare Resource and Research Unit (CRRU).

New challenges and opportunities for child care

Early learning and child care is undergoing unparalleled change in Canada today. Although most of the country’s supply of regulated child care survived the COVID-19 pandemic, child care emerged in a weakened state as financial and staffing crises severely affected the viability of services across Canada. As these challenges have coincided with the introduction of a new, ambitious federal pledge to build a universal Canada-wide child care system, new solutions to the policy conundrum of dramatically and rapidly expanding access to child care are very much needed for the program’s success.

In most of Canada, municipalities have never played a key role in child care. This paper explores whether municipalities could become a significant partner in enhancing access to the much more available, publicly funded, publicly managed, high-quality child care system now envisioned Canada-wide. This is timely, as a political commitment has been made to transform Canada’s child care situation from a market model with limited public funding and limited accessibility for parents to a universal, high quality, inclusive system. As Canadian child care in a policy and provision sense is still in its infancy, the possibilities for learning from experience and evidence are many.

Until 2021, there was no defined federal role in or funding for building a Canada-wide child care system, and provinces’ and territories’ policies have been varied and shifting. Despite some discrete advances, no jurisdiction has taken a sufficiently comprehensive approach to develop a workable system, leaving child care as a scarce and inequitable market service.

One important element of Canada’s market child care model has been that responsibility for creating the supply of child care services has been almost entirely a private one. This has meant that developing child care programs has been left mostly to private non-profit voluntary organizations and parent groups and to the for-profit sector, which runs the gamut from individual “mom and pop” centres to “big box” private-equity-backed corporate chains. [27] As a result, regulated child care is in short supply or non-existent in many locales; research shows that in 2022, almost half of children below school age lived in “child care deserts,”[28] with marginalized low-income, newcomer, and rural families especially left out.[29], [30]

In 2021, the federal government initiated the Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care (CWELCC) plan, setting out a framework by which the federal government and provincial and territorial governments will transform Canada’s child care market into an accessible child care system over time. Its first concrete step was to begin reducing parent fees substantially, a goal met, or nearly met, by all provinces and territories by the end of 2022. This significant change, however, has had the effect of bumping up public demand for more, and more equitably distributed, child care programs, turning a spotlight on the critical need for greatly expanded and more fairly distributed child care services.

It is here that the clear fit of an enhanced role for municipalities with a transformed early learning and child care system is most striking. The idea of a significant municipal role in child care is neither unique to Canada nor new within Canada. However, an analysis of such a role, where it exists both in Canada and beyond our borders, and of what it could achieve in a transformed Canadian child care system, has not yet been on the agenda. This paper is concerned with the potential role municipalities[31] (or municipal-level governments) could play in strengthening access to high-quality child care services. It discusses two main areas in which municipalities could be more extensively involved in Canada:

- local public management of child care supply and the service system, and

- public delivery of child care services.

The paper includes examples of municipal roles in several of the early childhood education and child care systems in the European Union, then discusses municipal roles in Canada. Finally, it considers the advantages that a heightened municipal role could play in strengthening Canada’s newest social program as it rolls out.

Why a municipal role in child care?

In many countries, the local level of government plays an important role in early learning and child care (ELCC).[32] In countries with child care systems that are further developed than Canada’s, such as Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, France, Slovenia, and Germany, the municipal level of government is most often responsible for managing and administering child care services, planning and supporting these services, and ensuring child care is available to meet parental demand. The operation of child care programs – both centres and regulated family child care where it is part of the system – is a second important municipal role; in many countries, most child care services are operated by municipal governments.

One of the drivers for a strong local role in child care in Western Europe’s relatively well-developed child care systems has been the concept of subsidiarity: an approach to social organization based on the view that the lowest-level competent authority available should take responsibility for an undertaking. A key benefit of applying this concept to local management of child care systems is that it enables democratic participation of community members, parents, and children to ensure that child care provision is responsive to local needs, since the local level “best understands the needs of local populations and where participation can most easily occur.”[33] This arrangement, however, will not be successful without balance: it is important to recognize that although communities are the place where the policies of senior levels of government are implemented “on the ground,” local responsibility is sustainable only if it is supported by both the high-level policy control and the financing that are generally the purview of more senior government levels. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has described how decentralization in early childhood education and care may lead to weak policy and to inequality unless there is close collaboration among all orders of government and civil society, as well as key roles for senior levels of government. Based on a wide-ranging analysis of 20 countries’ early childhood education and care systems, the OECD observed that

it seems important to ensure that early childhood services are part of a well conceptualised national policy, with on the one hand, devolved powers to local authorities and on the other, a national approach to goal setting, regulation, staffing, pedagogy and quality assurance.[34]

A 2023 report by the Jimmy Pratt Foundation in St. John’s, Newfoundland, posed the question “Why should municipalities play a role in child care?” and went on to answer it as follows:

Governments have tools at their disposal that not-for-profit organizations do not. They have access to demographic data to help them forecast demand for child care. They also benefit from economies of scale in the areas of construction, human resources, and administration. Governments can more easily use vacant public buildings for new projects. Generally speaking, public-sector centres are the best employers, providing the best working conditions for ECEs with less staff turnover, better working conditions and better benefits.[35]

International approaches to public management and public provision

Internationally, municipalities play two main roles in child care. The first is the public operation of child care services,[36] whereby municipal governments themselves deliver the services. The second is one of public management and administration of many aspects of local child care provision. This may include administering funds from senior levels of government; managing staffing; structuring community and parent involvement; assessing quality and implementing improvements; providing pedagogical input and management, in-service training, and professional development; forecasting demand; and – not least – planning and developing services.

The international examples of municipal involvement in child care that follow are all drawn from unitary countries – Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. These countries offer useful examples at least in part[37] because municipal governments generally have an expanded role in unitary systems. The examples are offered not as much to suggest that Canada should mimic Sweden, Denmark, or Norway, but to illustrate the role governments that are responsive to local needs can play in making a child care system function well. As the principal level of sub-national government in unitary countries, municipalities necessarily perform some of the functions that may be performed at a provincial or state level in a federation. When considering the application of the Scandinavian approach to child care management and provision to a federal country like Canada, the enhanced fiscal capacity of municipal government in a unitary context must also be taken into account.

Public management

In Sweden’s well-developed, mature child care system, municipalities have been responsible for child care policy and provision since 1975 when, with the introduction of the first national Preschool Act, child care became a mandatory area of municipal responsibility: “municipalities were obliged to take responsibility for [child care] expansion.”[38]

The recognition that adequate provision of child care is in the self-interest of local communities to ensure their sustainability, prosperity, and growth emerged during Swedish child care’s expansion phase. This was a key factor in the successful roll-out of Sweden’s child care system between 1970, when the major expansion was initiated, to the mid-2000s, by which time the number of child care spaces for preschool- and school-aged children had increased from 70,000 to over 750,000 – more than tenfold.[39] Barbara Martin Korpi attributes Swedish child care’s successful growth from the 1960s to the 1980s to this “municipalization”:

The state and municipalities undertook to provide an increasingly larger proportion of the financing, day care centres and play schools gradually came under the auspices of the municipalities. Municipalisation of nurseries received strong support from the municipalities themselves and the trade union organisations. The need for coherent municipal planning was the main reason behind the municipalisation process, as well as more even and higher quality combined with more secure financing. The staff wanted municipalisation in order to get more secure working conditions.[40]

Norwegian municipal responsibility for child care provision also dates to 1975, with Norway’s first Kindergarten Act.[41] The Norwegian national government made child care a children’s right in 2009, but it is still “municipalities and counties that are the key players in providing significant social and education programs including child care, education and health care,” with municipalities responsible for reaching specific targets set by the national government and for making local decisions within the national framework and objectives.[42]

The role of municipalities in public management of child care is similarly central in Denmark. The national child care framework legislation assumes that “the state has the overall responsibility, and municipalities are responsible for local organization [of child care] within the framework of the law.”[43] Danish municipalities not only create, supervise, and inspect centres but are responsible for managing parent involvement and administering funding, including the collection of parent fees. Municipal pedagogical experts work closely with educators on quality improvement on an ongoing basis, and local child care curricula are based on the national government’s early childhood act. Key decisions on matters such as program standards, however, are usually made at the national level. For example, the national parliament recently passed a new law strengthening staff-to-child ratios across all of Denmark.[44]

Public delivery

Municipalities in many countries also play a key role in the direct delivery, or operation, of child care as a public service.[45] In countries that have built relatively mature child care systems with universal coverage over the last 30–40 years, municipal operation of child care services is the norm, although there are also private non-profit and some for-profit provision almost everywhere. This is the situation in Austria,[46] Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Slovenia, Sweden, and elsewhere. The Canadian landscape is quite different, as the following section describes, as is that of other countries that rely heavily on market-based child care: the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands. In these countries, the operation and provision of services are primarily privatized, with hefty reliance on parent fees, as well as demand-side funding such as vouchers, benefits, and low-income parent subsidies to distribute public funds.[47]

Sweden provides a good example of a system with a high level of public child care provided by municipalities. It was during the period of Swedish child care’s rapid expansion that publicly operated child care services mushroomed, with municipally run centres built in old and new housing, as well as in a variety of public spaces and free-standing facilities. Korpi noted that

[i]n 1941 the municipalities ran around seven per cent of the few institutions existing at that time… By the end of the 1960s, the expansion of day care centres under the municipalities had clearly started. In 1970 almost all pre-schooling [i.e., child care] – 96 per cent – was municipal.[48]

The concept of government “steering” of child care provision, as used by the OECD in a 20-country thematic review of early childhood education and care provision, can be applied to municipally operated child care. This concept suggests that linking child care more closely to government is usually more effective than relying on the market.[49] Local government – which is well positioned to respond to local needs – can plan, locate, and design child care to address needs at the neighbourhood level, as well as consider cultural factors, child age groups, and parental needs, such as child care at non-standard hours. Responsiveness and equity are more elusive in child care markets than in more publicly managed models, and can be better achieved with appropriate government steering, including municipal service delivery.

Although recent research suggests that child care in the Nordic countries and in France has been experiencing “intense marketisation and privatisation development,’’ child care in these countries remains predominantly publicly provided, usually by municipalities.[50] In Denmark, municipally operated child care made up 80.2 percent of total provision in 2021 (including family child care); 11.2 percent of centres were “independent” (non-profit) and 8.5 percent were “private” (for-profit).[51] In Sweden, although private (both non-profit and for-profit) child care provision has grown, more than 70 percent is municipally operated.[52] In Germany, where child care provision is quite variable by state, about one-third is reported to be municipally provided, with most of the remainder non-profit or church-run.[53] Norway, where for-profit provision has been allowed to grow to represent a more sizable minority of services than in other Nordic countries, recently issued new requirements and accountability for for-profit operations.[54]

The role of Canadian municipalities in child care

Although there has long been some municipal involvement in Canadian child care, it has been quite limited, with models of municipal involvement remaining local and regional. Canada has mostly relied on the “third sector”[55] to “initiate and deliver child care – part of a long tradition of voluntary sector delivery of social and personal services,”[56] with mainly small or midsize entrepreneurs playing a sizable service-provision role in some regions and child care from “big box” corporations and sizable chains growing in the last decade or so.[57]

Outside Ontario, the municipal level of government has rarely assumed responsibility for the management or administration of child care services. Nor has there been much interest in municipalities operating child care services in much of Canada, with exceptions in Ontario, Alberta, and more recently, in British Columbia.

Ontario

Ontario municipalities have long played a unique role both in managing child care services – a role that has strengthened over the years – and in operating public child care (both child care centres and family child care) – a role that has diminished substantially in the last two decades. Municipalities have been an important aspect of child care in Ontario since World War II, when child care centres were set up for women working in war-related industries. Post-war, the municipal role was enhanced as municipalities began to share child care funding with the province to replace withdrawn federal funding.

A 1981 Ontario government child care policy paper stated, “The significant municipal role contributes to greater appropriateness of local services…and should be retained and strengthened.”[58] A 1987 policy paper, New Directions for Day Care, strengthened the municipal role in child care by increasing support for local planning, community participation, and local initiatives such as community needs assessments.[59] Ontario municipalities’ “local service management” role was mandated by a Conservative government in 2000, building on the network of Consolidated Municipal Service Managers (CMSMs) and District Social Services Administration Boards (DSSABs). These municipal and regional entities were established to oversee social services during a period of provincial social-service cutbacks, downloading, and amalgamation of municipalities.[60]

Today the Ontario government retains primary control over child care but delegates responsibility and some discretion to the 47 CMSMs and DSSABs. These are tasked with managing provincial child care funding, including fee subsidies for lower income families; paying a specified local share; conducting local service planning; and managing child care services. They have also voluntarily assumed other roles, such as quality assessment[61] and improvement, professional development, and research. Local service system managers may shape some aspects of their child care services within provincial rules and permission. Recently, some discretionary municipal policies, such as using the results of quality assessments to determine funding disbursements or choosing not to fund for-profit operations,[62] have been curtailed by the current Ontario government.

In addition to this mandated local service management role, Ontario was at one time the primary provider of municipally operated child care in Canada. During World War II, Ontario was one of two provinces to take advantage of the federal government’s offer to share child care centre operating costs, and its municipalities operated many wartime day nurseries. When federal support for child care ended after the war, a number of Ontario municipal centres remained open. In Toronto, the municipal government ran most programs for children below school age, leaving the school board responsible for care for older children. This post–World War II municipal involvement came to play a significant role in the development of child care in Ontario after the federal Canada Assistance Plan (CAP) was introduced in 1966, with its provisions that were to shape Canadian child care for more than 40 years.[63]

Municipal child care delivered a substantial minority of Ontario child care for many years, often prioritizing low-income families. As recently as 1998, 18 percent (18,143 spaces) of Ontario’s child care supply was municipally operated. This number has since diminished very substantially, as both the non-profit and for-profit sectors grew and many municipally operated services closed. For example, all of Peel Region’s 12 regional centres closed in 2012, all five of the Region of Waterloo’s centres closed in 2020, and by 2023 even the City of Toronto was only operating 39 centres and one family child care agency, down from 56 centres only a few years earlier. In 2021, only 16 Ontario municipal entities were operating 109 centres with 9,464 centre spaces (6,980 full-time spaces for children five years old and under, and 2,484 before- and after-school spaces for 4-to-12-year-olds) out of a total of 464,538 centre spaces for children 12 and under; 13 CMSMs and DSSABs operated regulated family child care agencies.

Alberta

Alberta is the only other province with a long history of municipal child care involvement. Unlike Ontario’s, Alberta’s municipal role was never mandated and did not include a local service management role. At one time, Alberta municipalities both delivered public child care and supported non-profit child care. In the 1960s and 1970s, Alberta’s provincial Preventive Social Services Act allowed municipalities to operate and support child care as an “approved preventive social service.” When the federal government introduced CAP’s child care provisions, some child care costs were shared by Alberta municipalities, the province, and the federal government, as in Ontario. But at the end of the 1970s, the Alberta government “largely removed municipal level governments’ financial capacity to develop, support and deliver child care services in response to community needs, and repositioned them as potential service providers or supporters of services, on a similar footing with private non-profit and for-profit organizations.”[64] Several of the large Alberta municipalities then sought, and the federal government allowed, direct transfer payments for child care through the CAP without a provincial contribution (a “flow-through”).[65]

In the mid-1970s, Alberta municipalities supported or operated 66 child care centres. At the peak level of municipal child care in Alberta in the 1980s, 11 of these centres were municipally operated by Edmonton, Calgary, Medicine Hat, and Red Deer, while Grande Prairie operated a family child care agency. By the end of the 1990s these had all been privatized, a shift attributed to the end of the federal CAP and its flow-through funding, along with the rise of the neo-liberal Reform Party.[66] Today, four other Alberta municipal entities – Beaumont, Jasper, Drayton Valley, and the Municipal District of Opportunity (a northern, primarily First Nations, community) – operate child care centres, all of which are local, rather than provincial, initiatives that arose after the demise of Alberta’s first phase of municipal involvement in child care.

British Columbia

In British Columbia, which has a different history of municipal involvement in child care, there is a unique and growing municipal role. In the absence of a provincial mandate for municipalities to participate in child care, the City of Vancouver has played a significant voluntary role in the planning, funding, and/or support of non-profit child care since the 1990s, when Vancouver established a Civic Child Care Strategy.[67] Over the last 30 years, Vancouver has developed and adapted its child care policy. Most recently, a ten-year strategy approved by City Council in 2022 outlines how the City “aims to support access to a new universal system of early care and learning led by provincial and federal governments.”[68]

The City of Vancouver’s child care strategy incorporates policy on child care directions, demand forecasting, creating services through a City-initiated non-profit child care agency, and negotiating for child care as a community benefit in the City’s land use planning and development process. It also provides capital grants to non-profit services, funded by the municipality mainly from development fees. The City of Vancouver does not operate any municipal child care centres.

Several of the other municipalities that make up Metro Vancouver also play a role in child care, although a less extensive one, supporting child care though zoning, demand measurement, and rental provisions; some have also developed child care strategies or included child care in their official community plans.[69] For example, suburban Surrey has adopted a child care strategy that includes planning, assessment, monitoring, and consultation with the community, as well as advocacy to the province for funds. The 2022 Surrey Community Child Care Action Planoutlines a proactive planning and initiating role to increase the supply of non-profit child care, although it does not raise the possibility of municipally operated child care.[70] The City of Richmond has undertaken multiple child care initiatives, including needs and assessment research, annual action plans, community advisory committees, needs forecasting, and – most recently – the development of publicly owned child care facilities with non-profit operators.

Building on Vancouver’s now several-decades-long experience in child care planning, the British Columbia government has supported child care planning as part of its effort to expand the supply of services. Using federal funds, the provincial government provided funds for child care planning and space creation to the Union of British Columbia Municipalities (UBCM) through the Child Care Community Planning Program and the Community Child Care Space Creation Program.[71] With these funds, UBCM engaged municipalities to develop local child care needs assessments, create child care services, and begin integrating child care into local initiatives and public spaces. For example, the City of Delta recently submitted a motion for consideration at the 2023 annual meeting of the UCBM “requesting the provincial government to provide funding to local governments to coordinate implementation of municipal child care action plans and projects developed through New Spaces Funding to support the expansion of child care.”[72]

Municipal operation of child care centres in British Columbia has been increasing markedly, with the provincial government identifying 63 municipal child care centres in 2021. Interestingly, non-municipal publicly operated child care in British Columbia is also increasing: the Province reported 302 publicly operated child care centres in 2021, including both centres operated by school authorities and those operated by First Nations.[73]

Other provinces and territories

A very small number of municipally operated centres are found in other provinces and territories. In addition to the Ontario, Alberta, and BC municipal child care provision already described, in 2021 municipally operated child care was identified in five other provinces and territories, with centres operated by three small rural Saskatchewan municipalities, two centres in Prince Edward Island, and three in New Brunswick.[74]

In the current climate of pressure for child care expansion, new kinds of municipal initiatives have also emerged. In southern Manitoba, for example, JQ Built, an organization created by municipalities, has developed a collaborative approach to designing and constructing important community infrastructure. The JQ Built team has worked with the Manitoba government to create and construct modular child care centres in rural and First Nations communities using federal and provincial funds. In addition to collaboration among municipal governments, part of the idea is to try out a “day care in a box” template for the rapid construction of child care facilities that can be adapted and replicated elsewhere.[75]

It is also of note that, while Newfoundland and Labrador municipalities are not permitted to operate licensed child care, a 2023 report by the Jimmy Pratt Foundation aimed at “driving public sector expansion” has recommended that the province

[a]mend the Municipalities Act (1999), City of St. John’s Act (1990), City of Mount Pearl Act (1990), and City of Corner Brook Act (1990) to allow municipalities to directly provide child care services.[76]

Could enhanced roles for municipalities make a difference in child care access in Canada?

Cities matter. This perspective motivated the Alberta-based Muttart Foundation’s proposition that it is “important to at least consider how municipal governments might participate more fully in the management, planning and delivery of early learning and care in partnership with the provincial and federal governments.”[77] This proposition was put forward before the introduction of CWELCC plan; it is even more salient today.

Given the pressure to expand child care in every part of Canada, there is substantial room for municipal governments to become more significant players in boosting access to early learning and child care, considering both public management and public provision as opportunities. The transformation of Canada’s scarce, inequitable, market-based child care provision system into one that is universal, high quality, inclusive, and equitable will necessarily be a long-term process. Thus, there is considerable room for learning from experience and evidence originating both inside and outside Canada. The international examples in this paper of municipal management and delivery of child care in the Scandinavian countries are provided not to illustrate off-the-shelf solutions but to indicate what Canada can learn from the experiences of other countries. Although the countries discussed are unitary states with different circumstances, there remains value in not only knowing why we do what we do, but also asking ourselves how we can do it better[78] by adapting good ideas to Canadian realities.

Pragmatically speaking, municipalities have, or could have, the capacity and tools to take a leading role in the local exploration and planning, improvement, development, and expansion of expanded child care services. As the local sites responsible for urban planning of residential, recreational, and commercial development, municipalities are in a prime position to assess, anticipate, and document local needs, and well placed to respond by making public buildings and land available. Adopting a proactive steering role could make municipalities key in the processes and possibilities of service expansion activities. As child care services expand to fulfill coverage targets, local public management also has the capacity to create efficiencies of scale while remaining sensitive and responsive to local needs.

It would also be logical at this time – in which a substantial, equitable expansion of regulated child care is urgently needed – for Canadian municipalities to undertake to operate more public child care services than the relatively few currently available across the country. This undertaking could, in the broadest sense, take inspiration from the “municipalizing” dimension of child care system-building in Sweden described by Barbara Martin Korpi, keeping in mind that such an undertaking would require support from senior levels of government – the federal government and provincial/territorial governments.

It is worth reiterating that there is no jurisdiction with a well-developed universal child care system in which publicly operated services are not prevalent – they are in fact usually the predominant mode of delivery. Policy analysts note that, although non-profit service providers will continue to play an important role in Canadian child care, they need additional support and funding. But it is unfair and impractical to assume that the non-profit sector has sufficient resources and capacity to fill the many large gaps in Canada’s child care supply. Thus, a mixed not-for-profit model that combines substantially more public child care and more, better-supported, non-profit child care has much promise.

The CWELCC plan is ambitious, setting out to transform child care provision from a scarce, costly market model to an equitably distributed, affordable, accessible, high-quality opportunity for all families and children – and a social and economic benefit to Canada. In support of the principle of accessibility, it has laid out targets for expanding the number of child care spaces Canada-wide. To live up to these aspirational principles, effective strategies, planning, and tools are indicated.

Strengthening the role of municipalities in child care through policy and practice is not the sole catalyst needed to successfully implement the envisioned universal system. But along with other policy fundamentals – such as sufficient, effective public funding of services, and solutions to the pervasive “wicked” child care workforce issues – more local public management and more public service provision by municipalities can be important factors in securing the early learning and child care system that so many have envisioned for so long.

The Municipal Role in Child Care in Ontario: What Should the Future Look Like?

By Gordon Cleveland and Sue Colley

Gordon Cleveland is Emeritus Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

Sue Colley is Chair, Building Blocks for Child Care (B2C2).

In the next few years, child care is set to become one of the largest areas of municipal government expenditure in Ontario, rivalling roads, transit, wastewater, and policing. By 2026, funding to make child care more affordable and accessible – most of it managed and distributed by municipalities – will reach about $5 billion annually in Ontario. This is more than double its level in 2018.[79] The Financial Accountability Office of Ontario believes that an additional 227,000 child care spaces will be needed beyond what is planned for 2026, so $5 billion is certainly not the final figure.[80]

On top of the operating funding managed by municipalities, substantial capital funding from a combination of public and other sources will be needed to create these new child care spaces, at upwards of $50,000 a space. The intent is that most of the new spaces will be in the not-for-profit sector, and municipalities will be heavily involved in planning and facilitating this expansion.

Since the funding and management of child care services will be such an important municipal government activity in the near future, it makes sense to look at the roles and responsibilities of different orders of government that are jointly responsible for what will happen.

Municipalities are mandated to have a central role in planning and delivering child care in Ontario; this municipal role is unique across Canada’s provinces and territories. According to Section 65(1) of Ontario’s Child Care and Early Years Act and the accompanying regulations, 47 single-tier (city) and upper-tier (regional) municipalities are designated to be service system managers for the delivery of child care services. Known, respectively, as Consolidated Municipal Service Managers (CMSMs) and District Social Services Administration Boards (DSSABs), they are now collectively referred to as service system managers (SSMs).

Most child care funding does not come from municipal own-source revenues,[81] but is provided to these service system managers by the provincial government. Since the signing of the Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care (CWELCC) agreement between Canada and Ontario in March 2022, the federal government is also a very significant funder of child care, in support of its strong policy vision of a universal and affordable system of largely not-for-profit and public child care services. There are also child care programs operating on 58 First Nations territories in Ontario – 73 licensed centres and 65 child and family programs. These child and family programs provide a range of services and supports to family and child well-being in Indigenous communities.

Looking backward: What provincial and municipal roles have been

We need to look both backward and forward to understand the appropriate roles of Ontario’s municipalities and the provincial and federal governments in relation to child care. Before the federal-provincial agreement of March 2022, municipal and provincial responsibilities were reasonably well defined. Right now, the roles of different orders of government are in considerable flux.

Situating the provincial role

The province has established a legislative framework for licensed child care,[82] and is responsible for licensing new programs and for monitoring and enforcement. It established the broad income and activity eligibility rules for child care subsidies. Until now, it has provided the large majority of funding for child care in Ontario, and in 2013, in consultation with municipalities, it established the funding formula that allocated early years and child care funding among the province’s municipalities. The legislation requires that licensed services implement the provincial play-based pedagogy How Does Learning Happen?

The Early Childhood Educators Act, 2007, established the College of Early Childhood Educators of Ontario. The College is the self-regulatory body for the early childhood education profession in the province. In 2015, the province also established and funded a wage supplementation program for some staff in regulated child care services. Starting in 2010 the province phased in and funded free full-day junior and senior kindergarten for children aged four and five during the school year, operated in schools by school boards. The program was fully implemented by 2014. Full-day kindergarten had important short-term negative impacts on the demand for licensed child care, destabilizing the sector.[83]

Situating the municipal role

As service system managers, municipalities across Ontario have been the direct providers of most of the public funding that child care operators receive, including child care subsidies on behalf of eligible parents, operational funding, and wage enhancement grants. They administer special-needs resourcing in their communities to allow children with special needs to participate in early years and child care programs. Municipalities have also been responsible for developing multi-year local early years and child care service plans to meet future needs. This planning is typically collaborative with local school boards and service providers, parents, and community representatives. In many municipalities, there are some child care services owned and operated by the municipality. Municipalities also provide support to local child care providers in areas such as governance, finance, operations, and service planning. In many communities, municipal authorities have developed and implemented quality-assessment programs that provide important oversight of safety and quality standards.[84]

The planning and system management roles of many Ontario municipalities are large. Outside Ontario, only British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec have more child care centres than Toronto, which has nearly 1,000. There are 11 Ontario municipalities that have well over 100 child care centres to monitor and fund.

The municipalities have had considerable discretion in the expenditure of child care funding. In particular, they could reflect local priorities in allocating money to child care subsidies versus operational funding or to lower parent fees versus operational funding directed at improving staff compensation. Some municipalities gave operating funding to not-for-profit centres only; others gave operating funding equally to both not-for-profit and for-profit centres.[85]

Toronto could decide, as it did, to allocate child care subsidies to eligible families on a first-come-first-served basis, refusing to choose which eligible families were most in need; other municipalities used different allocation rules. Municipalities could establish rules about which child care services should be preferred in contracts to care for subsidized children. By 2018, 16 out of 47 municipalities had decided, based on judgements of service quality, that they would only sign new purchase-of-service agreements with not-for-profit child care operators. Other municipalities made different decisions.

Toronto decided that financial accountability was best served by insisting that all operators with purchase-of-service agreements should submit detailed annual budgets justifying the fees they charged the City for the care of subsidized children. In contrast, many other municipalities decided that they were willing to pay purchase-of-service operators the average municipality-wide parent fee in each age category, without further financial documentation. In short, there was considerable municipal discretion in the way that general provincial child care policies were implemented. Municipalities were attuned to local needs and preferences, as determined by their local Councils.

Changes in the municipal role

The CWELCC agreement has begun to change almost everything about child care in Ontario. For the first time,[86] the federal government came to the table with very significant sums of money; by 2026, it will be spending more money on child care in Ontario than the provincial government does. Before these agreements were signed, the provincial government had been reducing expenditures on licensed child care, favouring instead tax expenditures on a child care credit that would subsidize parent expenditures on any form of care. The offer of federal money convinced the Ontario government to shift gears and apparently adopt the federal vision. This vision would transform Ontario child care from a service predominantly funded by parents to one overwhelmingly funded by governments, where licensed services are widely available to parents at a fee of $12 a day on average. Additional child care subsidies would reduce the parent fee for some families even further, bringing the average fee down to $10 a day.

The CWELCC changes are having important impacts on the municipal role. Municipalities no longer have discretion over the provision of operating funding to providers participating in the CWELCC program – they must provide exactly the amount of funding that replaces revenues lost by what was initially a 25 percent cut from the fee charged on March 27, 2022, and now is a cut of slightly more than 50 percent compared to that date. Ontario is now discussing a new funding formula to amend this revenue-replacement model,[87] but the rules governing the funding of each centre will still be determined by the province rather than by municipalities. Municipalities will become pass-through agents – deliverers of funding – rather than decision-makers regarding the local allocation of child care funding.

On top of this shift, Ontario has effectively frozen the total number of child care subsidies available, further reducing municipal discretion. In addition, Ontario has passed regulations eliminating municipal discretion about which centres should be preferred to provide services to subsidized children. Municipalities in Ontario previously had the discretion to use measures of quality as a criterion for their willingness to purchase child care services from operators; this is no longer permitted.

Moving toward universal, affordable, accessible child care

If Quebec’s experience is a relevant guide, it is likely to take at least 20 years before the early learning and child care system in Ontario is fully developed. It took about that long for the supply of child care spaces in Quebec to catch up with demand. What that means is that each Ontario municipality will be preoccupied for at least the next 20 years with managing the development of a universally accessible and very popular local child care system. These municipalities will be dealing with the turbulence associated with a system in which service demand exceeds service supply and in which issues of access, expansion, adequacy of funding, and quality require very regular attention.

What actions will Ontario need to take over the next 20 years?

- As demand for child care services increases, there will need to be more operational funding from governments. In Ontario, $5 billion per year will not be enough. If the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO) is right about the eventual need for over 227,000 additional spaces beyond those currently planned, both federal and provincial governments will need to come up with more annual money.[88] In the meantime, there will be shortages of capacity and waiting lists for inexpensive child care.

- Educators in child care centres are currently paid as if they had a high school education, instead of the two-year college diploma that is actually required.[89] It is becoming increasingly urgent to raise the compensation and working conditions of qualified educators; current compensation levels are insufficient to maintain and increase the supply. Colleges will have to graduate more new educators, and graduates who have left the sector will have to be attracted back.

- Non-profit and public child care facilities will need to expand much more rapidly than they currently are. Provincial and municipal governments will have to make significant planning decisions about priorities for expansion and will need to coordinate getting local permissions, new licences, and access to predictable operating funding. Either provincial or municipal governments will need to make loan guarantees to ensure non-profit child care providers have access to billions of dollars of one-time capital funding from private or public sources over the next decade. Organizations that can design and develop child care facilities will have to be mobilized, and there will need to be a major expansion in the number of not-for-profit or public organizations willing and able to operate child care facilities.

- The Ontario Ministry of Education has mandated that the municipalities prioritize expansion of child care spaces to low-income, racialized, Indigenous, francophone, new immigrant and special-needs children in the context of supply shortages. Meeting this goal will require increased numbers of child care subsidies and increased funds dedicated for children with special needs. It may also require public management of child care waiting lists.

Taking the actions required to meet the challenges of the next two decades cannot be done without full involvement of municipalities in the planning and administration of all aspects of the CWELCC system. It is inappropriate and counterproductive for Ontario to plan the development of the province’s child care system without consulting municipalities. However, that is exactly what happened in 2022 when Ontario signed the Canada-wide agreement with the federal government, including its detailed plans for multiple years of system expansion.

Since negotiating the CWELCC agreement, Ontario has changed its plans frequently. It has already made major revisions to the workforce compensation plans detailed in the agreement. It has zigzagged on system funding and management rules. It is anticipating substantial capital expansion without any capital grants for community spaces. If we want to know why Ontario has done such a poor job so far of designing workforce compensation supports, of planning system expansion, and of developing a new operational funding system, an obvious contributing cause would be its failure to develop these plans collaboratively with Ontario’s municipalities.

Recommendations for a municipal-provincial partnership in child care

Ontario has been slow in developing a new funding system for the radically altered child care system it is bringing to birth. So far, the province’s modus operandi is to issue a new plan and then ask for comments on an online, preset form. Much better would have been to involve municipalities in designing new funding rules with the following principles in mind:

- Operational funding that is predictable, indexed, and multi-year is a prerequisite to expand system capacity to meet local needs.

- Funding should be based on a consistent and equitable formula that reflects the true costs of local services.

- Operational funding should incentivize quality (through, for example, regular professional development, increased numbers of registered early childhood educators, adequate planning time, higher wages, benefits, and pension plans), should encourage parental involvement, and should cover new administrative requirements for providing information on costs, enrollments, and accountability.

- Funding and management rules need to guarantee the provision of sufficient data to public managers and need to ensure substantial financial and program accountability. Further, the funding formula should provide a flexible framework within which service system managers can operate that allows them to use the right mix of approaches to address unique local needs and circumstances.

Without a doubt, responsibility for child care and early years services is shared. Provincial legislation and regulations establish the framework within which the child care system will develop; therefore, changes in legislation and regulations occur necessarily at the provincial level. However, delivering affordable child care services so that they are universally accessible to meet the diverse needs of different families across Ontario has to be a collaborative, ongoing activity. Further, the province and the federal government have the money; municipalities do not. Property taxes will not rise as women’s labour-force participation and GDP rise, but provincial and federal income taxes will. Therefore, municipalities should not be expected to rely on the property tax base to share the costs of child care services with the provincial government.

The municipal role is different:

- Municipalities can and should be principal actors in planning the locations and characteristics of the rapid local expansion of capacity that will be necessary, including finding public lands, building new child care centres, and holding and managing some child care assets. The province should provide financial support for this critical municipal role.

- Municipalities are likely to have a prominent role in monitoring and assessing funding claims by operators, administering child care subsidies to low-income families, administering services for children with special needs, and providing funding both for family home child care and for child and family centres (typically branded as EarlyON centres). Municipalities will also be responsible for assessing the quality of services locally. And they will provide essential feedback to the province about what is and is not working for local providers and families.

- Municipalities should have substantial control over licensing decisions. This would include the decision to grant a licence based on the need for early learning and child care in a particular location as specified in the local municipal service plans. Currently, provincial licensing consultants have the power to grant exemptions from existing regulations to child care centres if they do not have sufficient qualified staff. These are called “Directors’ approvals.” Such exemptions are on the rise and really need to be curtailed. Municipalities should have a role in these kinds of decisions.

Going forward, it seems clear that action plans[90] negotiated every several years between provincial and federal governments will be the major system planning tool, establishing multi-year priorities for billions of dollars of federal funds. A new province-wide body needs to be formed to ensure that Ontario’s CWELCC action plans reflect municipal knowledge and priorities. It would involve large and small municipalities from different parts of the province, the Ontario Municipal Social Services Association, francophone and anglophone school boards, First Nations and other Indigenous representatives, and other key stakeholders, such as representatives from community colleges, the College of Early Childhood Education, the Ontario Coalition for Better Child Care, Building Blocks for Child Care, and the Association of Early Childhood Educators of Ontario, in discussing and deciding on multi-year plans with the provincial government.

If the transition of Ontario child care toward a universally accessible service is going to be successful, municipalities will need to be full partners in how this transition is managed. The municipal role in child care – unique to Ontario amongst provinces – has been and still is potentially a source of enormous strength. Now is the time to transform the shared provincial and municipal responsibility as regards to early learning and child care into a more productive and collaborative partnership.

Public Works: How Municipal Child Care System Management and Operation Can Help Solve the Child Care Workforce Crisis

By Rachel Vickerson and Carolyn Ferns

Rachel Vickerson is the Policy and Project Manager at Child Care Now.

Carolyn Ferns is the Public Policy Coordinator at the Ontario Coalition for Better Child Care.

A Note about Terminology: The term “early childhood educators” (ECEs) is used to describe individuals who have completed a one- or two-year post-secondary program in early childhood education. Every province, and Yukon Territory, has its own certification process that identifies the level of education required. Ontario is the only province in which Registered Early Childhood Educator is a legislatively protected and regulated title. There are also many staff working within child care settings who do not have ECE certification and may have completed a six-week orientation course or have no recognized credentials.

Introduction

This paper will focus on the role of municipally operated child care and how it can provide accessible child care built on a foundation of quality work environments for early childhood educators (ECEs), particularly within the new Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care (CWELCC) program. It will highlight several case studies of municipal child care programs in order to explore the policies and governance structures that enable these programs to provide, on average, better working conditions and wages than privately delivered non-profit or for-profit care and discuss how each level of government can support municipal child care and play a role in solving the ECE recruitment and retention crisis.

The current context of early childhood education

The federal government’s CWELCC plan includes a commitment to create 250,000 new child care spaces by 2025–26.[91] However, in every region of the country, these expansion goals are constrained by a child care workforce retention and recruitment crisis. Across the country, child care programs are struggling to staff their existing spaces and cite the lack of educators as a major factor preventing them from expanding.[92]

ECEs have long cited poor working conditions and low pay as deterrents to staying in the sector long-term. In the first cross-Canada survey of ECEs in 1991, respondents selected “providing a better salary” as the most important thing needed to make child care a more satisfying work environment.[93] While there have been modest improvements to wages in the last 30 years, 2021 Census data shows that early childhood educators and assistants working in child care centres only earned median hourly wages between $18.65 and $21.32 nationally, depending on the number of hours in the full-time work week.[94] This makes work in child care uncompetitive compared to occupations with similar levels of education and training.[95]

The challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated systemic issues facing the child care workforce. In a survey by the Association of Early Childhood Educators Ontario and the Ontario Coalition for Better Child care in 2021, ECEs reported increased stress with the onset of the pandemic, and 43 percent of respondents reported that they had considered leaving the sector since then.[96] The factors that motivate ECEs to stay in the field are similar across the country: ECEs want livable wages that recognize their qualifications and skills, compensation such as benefits and a pension, and a working environment that supports professional learning and career advancement.[97]

Recruiting and retaining qualified ECEs are not only necessary for expanding the availability of child care services, but are also crucially important for providing high-quality programs for children. For both accessibility and quality reasons, retaining a qualified, engaged workforce of ECEs should be a priority for governments at every level.

Role(s) of municipalities in child care management and provision

While the majority of child care in Canada is operated by the private sector (71 percent non-profit and 29 percent for-profit), in many parts of the country there is also a small amount of publicly operated child care. Public bodies that operate child care include First Nations, school boards, and municipalities.

Ontario is the only province in which municipalities are mandated to act as service system managers for child care and are responsible for the administration and funding distribution for licensed child care programs within their regions. Some Ontario municipalities also operate child care programs directly, although this role is discretionary rather than mandated. These municipalities are unique in their dual role of child care system management and operation.

In 2021, Ontario had 109 municipally operated child care centres, and the largest proportion of municipally operated spaces of any province or territory, although municipally operated centres also exist in smaller numbers in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Northwest Territories and Nunavut.[98]

Municipal child care in Ontario: Trend, countertrend, and a new provincial attack

The next section will use case studies to explore the advantages of municipal child care operation, especially for the child care workforce, and the potential that the expansion of municipally operated child care could have for stabilizing the sector, improving access, and ameliorating the workforce crisis.